Creating Enlightened Society: Compassion in the Shambhala Tradition

Judith Simmer-Brown

With the broader propagation of the Shambhala teachings that highlight the importance of creating enlightened society, it is natural to wonder what compassion means in a Shambhala context. In conjunction with Naropa University’s 40th Anniversary and the theme of “radical compassion,”[1] this article explores the unique contributions of the Shambhala teachings to cultivating and manifesting compassion in a complex, ever-changing world full of overt and subtle modes of suffering. The approach of the article is to provide a historical and cultural context for the Shambhala teachings and for their relevance to contemporary global crises, and to provide scriptural and commentarial support for the view of compassion as a motivation for creating enlightened society.

Buddhism has always been associated with compassion. The Buddha said that he instructed his monastics to go forth and teach “for the good of the many, for the happiness of the many, out of compassion for the world, for the welfare, the good and the happiness of gods and humans.”[2] Compassion teachings pervade all Buddhist lineages, and they are among the most compelling practices currently being pursued by Western practitioners. From mettā or lovingkindness practices to the brahmāvihāras, tonglen, and contemporary self-compassion and communal compassion practices, Buddhism has introduced profound and pragmatic ways for practitioners to become more caring and responsive to themselves and to others. As the Dalai Lama famously said, “We can reject everything else: religion, ideology, all received wisdom. But we cannot escape the necessity of love and compassion… This, then, is my true religion, my simple faith.”[3]

While there are many sources on compassion in Buddhism, very little has been written about the founding tradition of Naropa University, and the very special teachings of Naropa’s founder. This tradition of Shambhala [4] “is rooted in the contemplative teachings of Buddhism, yet is a fresh expression of the spiritual journey of our time. It teaches how to live in a secular world with courage and compassion” according to the Shambhala International website.[5] This paper will address Shambhala’s unique and visionary teachings on compassion and on creating enlightened society.

Shambhala History and Lineage

“While it is easy enough to dismiss the kingdom of Shambhala as pure fiction, it is also possible to see in this legend the expression of a deeply rooted and very real human desire for a good and fulfilling life.”

Chögyam Trungpa[6]

Tibetan Buddhism has always promoted powerful methods of personal transformation focused on transmuting the habitual energy of aggression, attachment, and bewilderment into compassion and wisdom. These methods begin with individual commitment to unmask the egocentric preoccupation that has, from beginningless time, caused such harm to others, as well as to oneself. With the realization that all beings, like ourselves, have the simple yearning to be happy and to avoid suffering, it is difficult to ignore the cries of the world. In the tradition of the bodhisattva, the compassionate meditations have served as the core of personal and societal transformation. In Tibet, these meditations serve as reminders that we can individually place the needs of others before our own needs, sparking the “turning of the tide” of egocentric concerns. These are at the core of Tibet’s treasury of compassion practices.

However, in contemporary society many agree that the factors that contribute to a degradation of dignity of human life are systemic, environmental, and complex, rendering merely individual efforts insufficient to the task. For this reason, the Tibetan Buddhist teacher Ven. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche (1939-1987) brought the transmissions of another important but lesser-known Tibetan tradition to his communities in the United States, Canada, and Europe. This is the tradition of Shambhala, named for the legendary enlightened kingdom, beloved in Tibet from historic roots to contemporary times. Through centuries of interaction with Buddhism, Shambhala became an esoteric transmission regarding the cultivation of “enlightened society,” universal in scope, compassionate in intention, and peaceful in its methods. Shambhala teachings blend influences from three primary sources: the Kālacakra-tantra tradition from 11th century India, Tibetan lore from the Gesar epic, and the Dzogchen tradition of the Nyingma.[7]

The Kālacakra-tantra teachings were given by the Buddha in the last year of his life to the king of Shambhala at Dhānyakaṭaka, in southern India in the place known as Amrāvati. Shambhala, literally “the place where tranquility is certain,” was a kingdom hidden north of the Himālayas in Inner Asia, “north of the River Sīta.”[8] King Sucandra (Dawa Sangpo in Tibetan) requested teachings from the Buddha that would allow him to reverse the traditional trajectory of renunciation, leaving home and responsibilities in order to pursue the path of dharma as a mendicant monk. He asked instead for teachings that would empower him to rule his kingdom in an enlightened manner, bringing wisdom and compassion together with strong leadership in order to directly benefit his subjects and his entire kingdom. His envisioned a completely enlightened society in which the citizens value the simplicity and beauty of human culture and harmonious community. The Buddha taught the king what has been considered the most subtle, sophisticated, and advanced dharma teachings in the world based on the Vajrayāna tradition of tantra.[9]

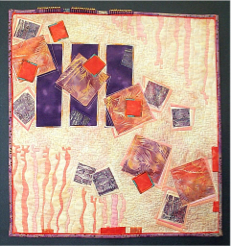

A second stream of influence with the Shambhala teachings comes from the indigenous pre-Buddhist Tibetan tradition of Gesar, the legendary warrior king who battled enemy forces in order to create a peaceful and harmonious society. Gesar was not a Buddhist, but his warriorship has been emblematic in Tibetan culture from early times and infused multiple aspects of later Tibetan Buddhist culture. In fact, under the influence of Buddhism, Gesar’s teachings became part of the strength, inspiration, and resilience of Tibetan Buddhist culture. The legend of Gesar is the last undiscovered epic in world literature, the first volume of which has recently been translated.[10] Through later Buddhist interpretation, Gesar was said to operate under the spiritual mandate of Padmasambhava to lead his kingdom against corrupting and divisive forces in order to create an enlightened society. Beloved by the Tibetan people, Gesar is considered a magical being whose inconceivable skill established the foundations of Tibet’s sacred culture. While his battles are described conventionally, later Buddhist accounts of the epic point to shamanic mastery of natural and human elements that make his leadership powerful. For example, in this perspective Gesar’s enemies are former tantric yogis whose arrogant misuse of the practice turned them against the dharma itself. Defeating them brings integrity and authenticity back to Tibet’s sacred practices while restoring the yogis to their dharma commitments.[11]

![Gesar | Illustration by Alicia Brown]()

Gesar | Illustration by Alicia Brown

Gesar

In modern times, the Gesar epic has been deeply influenced by Chinese culture from the Yuan emperors, bringing elements of Confucian political philosophy into Tibetan culture.[12] When Chögyam Trungpa taught about enlightened society, he drew from post-antiquity Sino-Tibetan notions of the philosopher-king who blended Tibetan indigenous[13] and Indian Buddhist elements together with Chinese medicine and astrology. From his perspective, these teachings have tremendous relevance in the contemporary west where respectful, visionary leadership is so rare and the need for it is so dire.

Thirdly, the Shambhala teachings are closely associated with the Atiyoga or Dzogchen lineages of Tibet. Dzogchen, or the “great perfection,” is considered the highest, most ancient and direct body of teachings of Buddhism, closely related to the pre-Buddhist, indigenous traditions of Tibet. The Great Perfection is not an outward goal for which we strive, but the fundamental perfection that is already present in the mindstream of beings, the completeness and goodness in the very nature of life. It cannot be perfected, because it is already inherently present, like the vast purity of the sky in which clouds may suddenly appear. The clouds cannot impede the sky or change its vastness, clarity, or accommodation. The focus of Dzogchen meditation practice is simply to realize that inherent purity and perfection of the basic nature. The great 20th century Dzogchen master, HH Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche wrote: “The practice is simply to realise the radiance, the natural expression of wisdom, which is beyond all intellectual concepts.”[14]

The tantric teachings of Dzogchen come from two Buddhist sources: the long transmission (ka-ma) of teachings traced back to the great masters of India, found in some of the essential tantras of the Nyingma lineage; and the short transmissions of treasure teachings (terma) hidden by the great adept Padmasambhava and his consort, Yeshe Tsogyal, to be revealed at auspicious moments throughout history.[15] Terma teachings are especially potent for practitioners in the Nyingma lineages, for the blessings are fresh and undiluted, and the message addresses particular circumstances and contexts in a particularly relevant way. In the Dzogchen lineage, certain realized teachers who have special qualities can discover the hidden treasure teachings through visionary means. They are called tertöns, or treasure discoverers; often it is their spiritual heirs who propagate the terma teachings, and these heirs are called terdak, or treasure propagators.

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche received Shambhala transmissions in both the long transmission, from his root guru Jamgon Kongtrul of Shechen, and as a tertön, through mind discovery in a series of visionary transmissions both in Tibet and the United States.[16] These teachings apply the ancient Kālacakra vision of enlightened society to the contemporary complexities of militarism, consumerism, and environmental degradation, as well as to the malaise and hopelessness that accompany them. He passed these teachings on to his dharma heir, Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, his eldest son who is the propagator (terdak) of his father’s treasure teachings. Together they have founded the Shambhala lineage.

The three main streams of influence on the Shambhala teachings weave together naturally in the culture of Kham and Golok regions in East Tibet. It was customary for monastic and lay culture in this region to weave together the Kālacakra, the post-antiquity Gesar epic, and Dzogchen practice and indigenous cultural elements into a single fabric of sacredness.[17] These streams became a living tradition under the influence of the great Jamgon Ju Mipham, the nineteenth century Rime (nonsectarian) master known for prodigious scholarship, instigation of Nyingma philosophical renaissance, and special connection with the Kālacakra-tantra and the Gesar epic. When he died in 1912, Mipham famously told his students he would not be conventionally incarnated, but would be reborn in Shambhala.[18] Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche was recognized in 1995 as Ju Mipham’s present emanation by His Holiness Penor Rinpoche, the head of the Nyingma lineage (1932-2009).

Trungpa Rinpoche had a particular passion and urgency about the transmission of the Shambhala vision and practices he had received. These were teachings of utmost relevance, for they provided a spiritual path with a social vision that shored up visionary solutions for the depression and hopelessness of our time. Having fled a medieval and isolated Tibetan society overrun by militant Communist China, he was deeply affected by the forces of materialism that drive contemporary international values, and he devoted his final decade of teaching to ways to ameliorate the violence and greed he observed. Central to his Shambhala teachings was the importance of “enlightened warriorship” based on gentleness and courage.

Warriorship in the Shambhala Lineage

“A true warrior is never at war with the world.”

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche

The Shambhala teachings are based on the warrior traditions of Asia, including cultures of India, China, Japan, and Tibet. While they reject the outward violence and unscrupulousness of the combat fighter, the Shambhala teachings embrace the discipline of the warriors’ training and the bravery and confidence necessary to sustain the strength of constantly facing challenges. Trungpa Rinpoche wrote:

Warriorship here does not refer to making war on others. Aggression is the source of our problems, not the solution. Here the word “warrior” is taken from the Tibetan pawo, which literally means “one who is brave.” Warriorship in this context is the tradition of human bravery, or the tradition of fearlessness.[19]

In this, the Shambhala teachings embrace the Tibetan folk hero Gesar, who exhibited bravery without aggression.

We live in an era where such bravery is necessary, for we are faced with daunting problems that can easily give rise to aggression on the one hand or hopelessness and depression on the other. The forces of militarism, globalization, and environmental degradation have weakened the fabric of our human communities and have undermined the life-force (sok) of individuals, rendering them helpless. The path of the warrior requires that we not give up on humanity or the earth community. Instead, we must raise our gaze to look carefully and reflectively at our communal human life and identify how we can be of help. The answers to the world’s problems will come from within our everyday experience, not from ideologies, political philosophies, or economic theories.

It is always assumed in the Shambhala teachings that compassion is the motivation of the warrior, though the way compassion is spoken of differs somewhat from the Buddhist teachings alone. In this essay, we will explore the core teachings of the Shambhala teachings in order to trace the contours of its presentation.

It is important to understand the cosmology and the Shambhala lineage for context. According to Kālacakra-tantra lore, the future of humanity will be increasingly threatened by barbarians (lalo in Tibetan), harbingers of the decline in the quality of life and of the increase in warfare, greed, and environmental destruction.[20] In the meantime, the lore speaks of the teachings of Buddhism as guarded and protected by a lineage of seven enlightened kings (dharmarājas) and twenty-five bodhisattva kings (kalki, or rigden) who protect the Buddhist teachings and guard the dignity of humanity under duress.[21] Each of these kings was predicted in the Kālachakra to live one hundred years. Eventually, when the forces of the degenerate age advance and the world descends into intractable violence and greed, the twenty-fifth Kalki (Rigden) king will appear with his enlightened army to bring about a new Golden Age, restoring the peace, harmony, and humanity of the world.[22] Various predictions from the Kālacakra traditions suggest this will occur in the 25th century, though others suggest that the degenerate forces are accelerating this time sequence.

In Tibet there are those who take these teachings as apocalyptic, vilifying the Muslim sources that threatened 11th century India and Tibet, but in the Shambhala lineage they are understood quite differently. In the contemporary Shambhala teachings, the forces of degeneration are already apparent, rendering gentle warriorship a timely response. With the help of the Kālacakra-tantra and Shambhala teachings, trained warriors are not daunted by the degenerate age. Instead, they find power and clarity in the midst of chaos and see the basic goodness and humanity in every situation. They are resilient in the midst of challenge, contented in the maelstrom of greed, and peaceful in the face of aggression. Their tantric training shows them how to turn the distractions of the life of a householder into a good human society. Their enlightened army wields weapons of kindness, strength, and wisdom to invigorate the life force of their communities and the world.

Basic Goodness

“The world is in constant turmoil because beings have not discovered their basic goodness.”

Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche[23]

The secret teaching of Shambhala sounds simple, and it is. It is the teaching of basic goodness, domine sangpo.[24] Human beings are good. We are complete, unmistaken, and there is nothing we lack. No matter what happens to us, no matter what we do, our underlying motivations are based on human feeling, the human heart. Everything that arises—doubt, fear, irritation, boredom—is an expression of that goodness. This is called “the great cosmic secret” transmitted by King Sucandra to the subjects of Shambhala.

The essence of all beings from beginningless time, this universal truth has always existed. It transcends the notions of good and bad; therefore it is primordial. It is beyond time and space; therefore it is inconceivable. It surpasses thought and nonthought; therefore it is remarkable… This rare human gift is at our fingertips day or night, whether we are walking, sleeping, or talking. It constantly pulsates within our being, ever transmitting wakefulness that has never known doubt or fear.[25]

The teaching of basic goodness is not a tenet or article of faith; it is presented as a quality that must be experienced. The Kālacakra says, “The nature of the primordial cannot be expressed in words, but with the eyes of the master’s teaching it will be seen.”[26] We can speak of basic goodness as much as we like, but without a direct experience of it, there is little understanding.

A direct way to experience basic goodness is through the sitting practice of meditation. We are taught by a lineage teacher to synchronize body and mind so that we can experience nowness, the present moment. This simple practice is an expression of accepting ourselves, our experience, and the world without judgment or bias. Then we can experience the goodness of our humanity.

According to the contemporary Shambhala teachings, the most daunting aspect of the degenerate age is the endemic sense of worthlessness and hopelessness that most people feel, no matter what cultural environment they may inhabit. We have given up on human nature and human society. While we may find exceptions in a few remarkable people, we feel that most humans, especially ourselves, are disappointing and inadequate. We are convinced that society especially is flawed. The 20th century confirmed our worst opinions about how humans behave in groups, and the 21st century is making strides to intensify that view.

These self-defeating views contribute to the dilemma of modern life. Our inner defeat leads to external disaster, and vice versa. The Shambhala warrior sees that the true antidote to the degenerate age is found in deep investigation of human nature through meditation. Then we see that the true nature of basic goodness is never distorted by circumstances, and that impurities are merely temporary ripples.

The Genuine Heart of Sadness

“Sadness is precisely the heart of warriorship.”

Chögyam Trungpa[27]

When we sit in nowness, we discover a kind of nakedness in our experience where we just are. We are not doing; we are being. This does not mean we have no thoughts or emotions. It means that whatever is occurring in our minds happens against a backdrop of utter simplicity, openness, and immediacy. There is no exaggeration and no minimizing. Everything is very straightforward.

This experience, however, is not merely a blank or vast empty sky. We discover this simplicity by tasting our own human heart, which is an experience of what is called the “genuine heart of sadness.” We find ourselves with ourselves, with all our storylines and habits, all our misgivings and hopes, and we are just there. Fundamentally, there is nothing happening. Within the space of that moment, we feel a quality of tenderness, vulnerability, and unconditional sadness. It is a poignant moment in which we are most in touch with our genuine humanity.

The genuine heart of sadness comes from feeling your nonexistent heart is full. You would like to spill your heart’s blood, give your heart to others. For the warrior, this experience of sad and tender heart is what gives birth to fearlessness.[28]

The sadness described here is not sadness about anything in particular, but is a constant companion as a kind of subtle mood. It is distinctly different from depression in that it involves a kind of tenderness that makes us more open to others, rather than wishing to withdraw into ourselves. The tenderness is about feeling our own experience and being touched by the beauty of human life. It is always there, not dependent upon circumstances, and it is never tragic. “Whatever you do to try to forget that sadness—sadness will always be there. The more you try to enjoy yourself and the more you do enjoy, nonetheless there is still the constant sadness of being alone.”[29]

The experience of the genuine heart of sadness has tremendous poignancy and joy as well. It is associated with aesthetic appreciation, being touched by the beauty and preciousness of human life. The samurai traditions of Japan place tremendous emphasis upon this kind of subtle and pervasive sad enjoyment. While appreciating the vividness of sense perceptions—of the placement of a stone in the garden, of the taste of bitter tea on the tongue—sadness about the transitory and vibrant beauty of the moment fills our empty hearts.[30] In this experience, we discover our humanity in a personal and intimate way.

The warrior joins sadness and delight together as a way to taste sadness rather than indulging in it. That is authentic tenderness, the experience of human goodness. As Trungpa Rinpoche wrote,

you should feel that way with everything you do. Whether you have a good time or a bad time, you should feel sad and delighted at once… Joining sadness and joy is the only mechanism that brings the vision of the Great Eastern Sun.[31]

The Great Eastern Sun is the full bloom of Shambhala vision of basic goodness and its manifestation as enlightened society.

Sadness and Bodhicitta: The Seed of Compassion

“The warrior’s duty is to generate warmth and compassion for others.”

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche

The experience of the genuine heart of sadness is an aspect of what both the Buddhist and Shambhala teachings speak of as bodhicitta, the awakened heart or the supreme thought. Bodhicitta is the topic of many Indian Mahāyāna texts, from the Prajñāpāramitā-sūtras and Saṃdhinirmocana-sūtra to the śāstras of Śāntideva and Kamalaśīla. No Buddhist teaching is complete without an extensive exposition of bodhicitta, for the tender motivation to benefit beings that is generally associated with relative bodhicitta is always coupled with the recognition of the ultimate insubstantiality and interdependence of all phenomena, a recognition associated with absolute bodhicitta.

Bodhicitta teachings became foundational in Tibetan Buddhism from the time of Ātiśa in the 11th century, and sources on bodhicitta abound in the Tibetan tradition. Śāntideva is considered the most venerable source of exposition of bodhicitta, and his 8th century composition, the Bodhicāryāvatāra, the entrance to the way of the bodhisattva, is the most popular Indian text in Tibet. As Śāntideva famously said of compassion,

All the joy the world contains

Has come through wishing happiness for others.

All the misery the world contains

Has come through wanting pleasure for oneself.[32]

This quote has become a slogan used by many Tibetan teachers, often glossed as “If you want to be miserable, think of yourself. If you want to be happy, think of others.” Throughout Śāntideva’s presentation, bodhicitta is described as the motivation to benefit others embedded in the recognition that other beings do not inherently exist and that their relative happiness cannot be separated from our own. His luminous verses guide the practitioner to transform personal preoccupations and fixations into compassionate care for others.

In the Sakyong lineage of Shambhala, Śāntideva is also beloved, serving as the foundation for most of the teachings on compassion. [33] Bodhicitta is nicknamed “the supreme thought,” lhaksam in Tibetan, which means that compassion and care for others are the pinnacle of human life, the “most supreme thought that the mind could possibly have.” [34] Lhaksam is spontaneous and natural, arising from the best of human nature, basic goodness. It is also considered the seed of enlightenment, for the essence of Buddhahood is wishing perfect happiness for all.

Such an attitude takes bravery, and so those who commit to bodhicitta are considered to be bodhisattva-warriors, those for whom their love is greater than their fear. When confronting the challenges of life—from life-threatening illness to warfare to disasters—they are the ones who choose not to retreat into mere personal survival, but who recognize that suffering affects everyone. They are the ones who are willing to work for the greater good of human society, seeing the fundamental potential of human life. They know that individual, personal happiness is not possible and that our human life must involve placing the happiness of others as primary. When bodhisattva-warriors have a terminal illness, they do not just retreat into their rooms, but start a support group for others with the same illness. When disaster strikes, they do not merely bail their own basements but organize teams bailing the flooding in the streets and preventing future floods.

This care for others is deeply motivated by the sadness the bodhisattva-warrior feels when encountering suffering, especially unnecessary suffering. This is not a tragic sadness, but recognition of how suffering works in human life.

In a moment of horror, one realizes that there is no source of this pain. The suffering is completely unnecessary. It would be another matter if there were, in fact, a self that was causing it. However, the only source—if it can be considered to be a source—is the mind’s confusion.[35]

Bodhisattva warriors feel the poignancy of the human condition, sadness for unnecessary suffering mixed with joy of connection with and care for others, and this becomes a motivating force in working for the benefit of others. “When the supreme thought occurs in the mind, one becomes fearless and brave,”[36] especially in working for the benefit of others.

The bodhisattva is a warrior because feeling the pain of others does not end the journey. “Instead of overwhelming and defeating us, the plight of human existence has the power to spark our deep-seated human valor and nobility.”[37] The challenge of helping the world becomes a life-giving purpose that uplifts and cheers the warrior, even while sadness touches her heart. Her fundamental inspiration comes from the personal experience of basic goodness, and her confidence comes from affirming this goodness throughout life.

The Supreme Thought and Enlightened Society

“Our hearts long to beat together.

Naturally, there is warmth, kindness, and love.”

Sakyong Mipham[38]

There is a slightly different emphasis in how teachings on bodhicitta are used in Shambhala, and the key is a larger, more societally-oriented motivation. Generally speaking, the compassion teachings in Buddhism emphasize individually working to benefit other beings, one at a time. The Shambhala teachings speak of social benefit—creating a society that highlights human goodness and ripens the capacity to manifest that goodness in community. The purpose of warriorship is to create an enlightened society.

The emphasis on societal happiness influences the Shambhala reading of Mahāyāna Buddhist history. It is well known that the Gupta period in India (320-700 C.E.), during which Mahāyāna flourished, was a classical age of Indian art, commerce, and culture.[39] As Sakyong Mipham observes,

the dynamic power of raising the supreme thought of bodhicitta to benefit others created a flourishing culture that celebrated human goodness and extolled the beauty of the world. This transformed Buddhism from an individual pursuit to a cultural pursuit. The arts and philosophy blossomed. We Shambhalians should draw great inspiration from the tradition of the Mahayana. It is part of our heritage.[40]

From a Shambhala point of view, when we embrace bodhicitta and the path of warriorship we enjoy the same possibility of celebrating community and culture, developing the arts and philosophy, and nurturing a new golden age of humanity.

The reason for the emphasis on society is found in the basic goodness teachings themselves. If all beings are basically good, a fundamental tenet of Shambhala, this means that human society is also good. In Tibetan, this is expressed as mi sipa sangpo: sangpo refers to the nondual sense of goodness or completeness (as opposed to yakpo, which means good versus bad)—intrinsically good. Mi is “human.” Sipa usually refers to the confused aspect of human life, saṃsāra, suffering. In this context, sipa refers to connectivity and community of all beings, full of the “desire to communicate, touch, and love one another.”[41] It refers to the universe of relationships, and even to politics, usually considered to be irredeemable but in this case “possible” to awaken into deep goodness. Those polluted elements of human life are, in their intrinsic nature, awakened, harmonious, pure, and full of possibility.[42] Society is basically good, already, in its very nature.

This means that the Shambhala teachings are not utopian. They are not referring to a future society in another place, another time, with another model. Enlightened society is the human society in which we already live; it is the society where everyone lives. We only need to awaken to the fundamental goodness and wakefulness embedded in the fabric of humanity. Everyone wishes to raise their children in an environment of peace and harmony, in which the customs and traditions of the family and community are passed along to the next generation. Every culture has its celebrations and ceremonies, its rites of passage, and its meaningful work. Every community takes pride in its food and crafts, its manufactured goods and trade, its hobbies and occupations. Even communities held hostage by warfare or sectarian strife, pitched into flight as refugees, or secularized by rapid industrialization and urbanization, have a longing for these cultural practices, and these communities are all evidence of the inherent enlightenment of society, according to Shambhala.

The Warrior’s Training in Compassion

“The essence of warriorship, or the essence of human bravery, is refusing to give up on anyone or anything.”

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche[43]

Like Buddhism, the warrior’s compassion practices involve supreme thought (bodhicitta) and lovingkindness practices, as well as sādhana practices that take the basic goodness of humans and of society as their object. The warrior commits to the sacred outlook (daknang) of seeing basic goodness in oneself, in others, and in society through formal vows and sādhana practice.[44] These are practiced, however, with special attention to the core Shambhala transmission regarding the life-force of humanity.

These teachings feature the yogic dimension of warrior training—a unique way of bringing yogic practice to societal benefit. The Shambhala teachings state that one of the causes of the current degenerate age is the weakened life-force (sok) that is core to the quality of life of individuals and communities.[45] In Tibetan medicine, yoga, and cosmology, the life-force is a psychophysical element in our ability to connect with inherent enlightenment or basic goodness and have harmony with others. If our life-force is low, our meditation practices—no matter how profound—will be of limited success. In the Shambhala teachings, the life-force is enhanced by the experience of lungta, literally “wind-horse,” bringing the vitality of the warrior’s horse into energetic connotation. Lungta is closely related to the practices of ch’i in China and prāṇa in India, arousing psychophysical energy coursing through the body.[46] Lungta is an actual warrior mind-body practice enhanced by a combination of lineage blessings, community life, and healthful lifestyle. Teachings on lungta are associated with both the Buddhist and indigenous shamanic traditions of Tibet and are linked with the dralas, or divine beings who protect the lives of individuals and communities.

While the name drala literally means “gods against enemies,” in the Shambhala teachings dralas protect against anything that jeopardizes the life-force of humans.[47] Dralas are closely related to the Rigdens, the bodhisattva kings of the Kālacakra-tantra. Humans can reawaken their life-force by drawing upon the blessings of dralas found in a visionary realm, in the natural world, and in the human body and mind itself. Dralas can also be human saints, bodhisattvas, who work tirelessly for the benefit of others. Through the blessings of the dralas, human lungta can strengthen and radiate, attracting and nurturing the continued influence of the dralas.

Fundamentally, however, drala is not a deity. Drala is the power of things as they are in the world and especially in our own beings—our own wisdom, our ability to connect directly with how things are in our experience. We might say that drala is our life-force, and it is found in gentleness and kindness rather than aggression.

But true magic is the magic of reality, as it is: the earth of earth, the water of water—communicating with the elements so that, in some sense, they become one with you When you develop bravery, you make a connection with the elemental quality of existence.[48]

Altogether, drala is the magical, synchronistic aspect of the world when seen without the limiting influence of merely self-centered perspectives. Magnetizing drala and raising lungta are the fundamental practices of warriorship.

When a warrior trains, Buddhist practices of śamatha-vipaśyanā meditation are foundational for connecting her with basic goodness. In addition to these practices, however, those that rouse lungta and attract the dralas are especially important, for they strengthen the confidence (ziji) of the warrior. In the degenerate age when humans become quickly discouraged or exhausted, this confidence brings a resilient compassion that can fulfill the vow to create enlightened society. These practices include meditations, ceremonies, warrior practices, and community celebrations.

When invoking drala and arousing lungta, the world becomes alive, vibrant, and sacred. “When you invoke drala, you begin to experience basic goodness reflected everywhere—in yourself, in others, and in the entire world.” [49] This experience fills the warrior’s mind with possibilities, and problems do not seem intractable anymore. The fundamental goodness and healthiness inherent in circumstances seem more apparent, and an ancient optimism and vitality bloom both within the warrior’s mind and within the circumstances themselves. This experience brings greater likelihood of finding allies and collaborators and of discovering organic solutions for society’s deepest difficulties.

Creating Enlightened Society

“The warriors approach is that, rather than trying to overcome the elements of existence, one should respect their power and their order as a guide to human conduct.”

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche[50]

The ultimate commitment of warriorship is to create enlightened society. At first, this commitment might seem almost messianic, invoking the aspiration of a crusader. But that approach is actually ego-centered and aggressive, manifesting more conventional than mystic. The crusader’s approach to social change is the most common and has not been successful. Instead, the warrior begins a journey of personal transformation first, and then continues this journey with further magical and actual engagement with the natural elements of existence. This approach discovers that “creating enlightened society” is seeing the inherent, unacknowledged sacredness of society and the world and becoming harmoniously attuned with it. It is a journey that joins yogic, relational, and societal dimensions.[51]

This journey begins with investigating the fundamental nature of humanity, identifying whether basic goodness is true and clear. How we feel about ourselves has a tremendous impact on everything we are and do.

When we feel goodness, a shift occurs: We get curious, which sparks care. We begin to see goodness happening in so many ways—rational and irrational, visible and invisible, and through signs, words, and examples. From that arise virtues like patience, exertion, and generosity.[52]

When warriors develop confidence in basic goodness, they become stakeholders in the society in which they live, and their activities are committed to bringing out the goodness of those societies. Becoming stakeholders depends upon appreciation, not merely critique.

Still, bringing out basic goodness in society is not a quick fix. It requires tuning into our communities and identifying ways to help its members to awaken to basic goodness. The gateway to basic goodness is through feeling, through affirming that our sense perceptions and emotional undertones are accurate, authentic, and worthy of respect. It is impossible to tune into feeling when we are speedy, and so finding time to connect to ourselves and to others through feeling is foundational for creating enlightened society. Sharing joy, sorrow, tenderness, and excitement builds relationship with others; learning to truly listen to others is the key. Doing so with kindness and gentleness ensures that we can honor our connection with others in a way that builds genuine community.

The foundation of creating enlightened society is relational, especially through our intimate family relationships. The Shambhala household is the unit of enlightened society, the matrix that provides the opportunity for the everyday practice of kindness and shared humanity. Trungpa Rinpoche wrote, “I learned a great deal about the principles of human society from the wisdom of my mother.”[53] Parenting puts us directly in touch with this intimacy, the ground of generosity and nurture of confidence in basic goodness. The Shambhala teachings include practices that cherish the household and hearth, as well as the relationships we develop with our spouses, children, and families.

Families and communities connect with each other through the ceremony of daily life—formally through celebration of holidays, religious and secular, and informally through the rhythms of the life stages, calendar, and seasons. Civic life routinely acknowledges community in a variety of ways, through governance, commerce, education, and change. Whether through the farmers’ market, the opening of a new library, sporting teams’ events, graduations, or funerals, communities have a way of acknowledging who they are and what they want to be. By bringing forward the intention to foster human goodness, warriors can contribute to ceremonies that create community contexts of meaning. They can infuse these ceremonies with kindness and appreciation in order to strengthen the fabric of connection.

For that matter, when the warrior begins to experience the sacredness of life, then all life is a ceremony. Every interaction is special. Each meal has specialness in its preparation, its enjoyment, and its cleanup. Going to work is joining the ceremony of the workplace, and returning home reactivates the ceremony of household and family. Everyday life is an opportunity to appreciate the inherent goodness of human life and human discourse, no matter how many people it may involve. The warrior can be present for life, and when doing this, the huge reservoir of lungta that animates life awaits.

When life is viewed in this way, the warrior has an opportunity to choose how to participate in the global ceremony of human life. How does this influence our buying patterns, our relationship with our natural resources, our responses to threats and attacks? The warrior can choose a life ceremony that considers long-term effects on the planet and its inhabitants. Sakyong Mipham writes,

what happens next on earth is totally up to us. If we are willing to work for a wholesome future, then humanity’s future truly does lie in our hands, for it will come about only through manual labor powered by our illumination. This creates a twinkle in the eye, brings a smile to the lips, and broadens our sense of conviction. In this light, humanity’s future can occur because we are willing to hold it in our own hands.[54]

Because current circumstances represent the ceremony of a kind of spiritual sleep and denial, the biggest responsibility of the warrior is to join with others to change society’s ceremony to one that honors, respects, and loves all of humanity. The future ceremony of society will be determined by what values we put in place.

Conclusion: Gentle Urgency

“The world does need your help so badly, very badly. So, on behalf of this world [smiling], I would like to request you to come and do something about it.”

Chögyam Trungpa[55]

From certain perspectives, this kind warrior training might be viewed as having little effect on the cataclysmic challenges of contemporary life. A critic would suggest that developing lungta and compassion is an anemic contribution to creating enlightened society, contributing few concrete solutions to the current crisis. But Shambhala is part of a worldwide “engaged Buddhism” movement that suggests a new approach, one that does not fall into adversarial methods or quick fixes. It is more of a paradigm shift about what it looks like to systemically change the basis of conflict. Spiritually-based social engagement like this suggests that the problems of our time belong to us as well, and that there can be no change without personal transformation.[56] We cannot simply create an alternative system that works; instead, we must use our understanding of the disease or symptom as a way to grow personally and societally toward more caring, penetrating compassion.[57]

One of the hallmarks of engaged Buddhism is giving up an adversarial approach. The basis of the analysis is different: there are no clear enemies. Thich Nhat Hanh writes, “Where is our enemy? I ask myself this all the time.”[58] For the Shambhala warrior, the enemy is not external. Instead, warriors battle their own fear and disheartenment. With confidence in basic goodness, the fundamental impulse to demonize others is put to rest, providing a completely different ground for activism.

Decades ago, in a penetrating essay he wrote shortly before being nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, the Dalai Lama asked the question, what are the real solutions to widespread warfare and violence in the world? If violence could be ended through waging war, then we should turn every resource of our world toward warfare and not rest until violence is defeated once and for all. But, as the Dalai Lama observed, we have tried that over and over again, and this has not been the solution to violence. He writes, “The time has come to try a different approach. Of course, it is very difficult to achieve a worldwide movement of peace of mind, but it is the only alternative. If there were an easier and more practical method, that would be better, but there is none.”[59]

The Shambhala tradition provides the basis for a powerful transformation of the motivation that seeks the welfare of the world and asks its citizens to step in and find a tangible, enduring way to help. Some Shambhala warriors have become activists; many have become leaders and visionaries in their fields. Most have been inspired by the dignity and beauty of everyday human life and have found ways to contribute to the long-term goal of enlightened society. They partner with others outside of Buddhism who share the vision of selfless service of the bodhisattva warrior, understanding that true compassion has never been the sole property of Buddhism or Shambhala. Through the transmissions of the Shambhala lineage, warriors have resilience and stamina and an ancient optimism about human potential. Within daily practice, they enjoy themselves by celebrating human capacity through appreciation of beauty through the arts, of human connection through community, and of wisdom through the cultivation of curiosity and investigation of the world. This means meeting friends new and old over coffee, having dinner parties and family celebrations, organizing community events, and going back to school for more education. Done with the proper attitude, these activities inspire confidence in the basic goodness of humanity. They also have the potential for contributing to the long-term goal of creating enlightened society.

Notes

[1] See the University website for information about the Radical Compassion Symposium that celebrates forty years of compassion work: http://www.naropa.edu/40/radical-compassion/. This paper was originally prepared for the Experts’ Meeting of the Uberoi Foundation for Religious Studies, held at Naropa University in September, 2014.

[2] Vinaya IV.20.

[3] Dalai Lama, The Ethics for a New Millennium (New York: Penguin Books, 2001), Chapter Sixteen.

[4] This paper uses the Anglicized version of the name, Śambhala, as that is what is generally used by this tradition in western settings. The term is Sanskrit; Tibetan is dejung (bde ‘byung).

[5] “Shambhala Vision,” (accessed July 16, 2014). http://www.shambhala.org/about_shambhala.php.

[6] Chögyam Trungpa, Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1984), 27.

[7] Other influences not treated in detail here are Confucian and Hindu Purāṇa sources and indigenous apocalyptic lore.

[8] The Sīta River is sometimes identified with the Tarim River in Eastern Turkestan. Shambhala is considered north of Tibet, Khotan, and China—which places it north of the Tian Shan. John Newman, “Itineraries to Śambhala,” Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre, Jose Ignatio Cabezon and Roger R. Jackson, ed. (Ithaca: Snow Lion, 1996), 487.

[9] For further information on the Kālacakra origins of the Shambhala teachings, see: Khedrup Norsang Gyatso, Ornament of Stainless Light: An Exposition of the Kālacakra-tantra (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2004), 1-20.

[10] Robin Kornman, Sangye Khandro, and Lama Chönam, The Epic of Ling: Gesar’s Magical Birth, Early Years, and Coronation as King (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2012).

[11] Robin Kornman, “The Influence of the Epic of King Gesar of Ling on Chögyam Trungpa,” Recalling Chögyam Trungpa, edited by Fabrice Midal (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2005), 356.

[12] Ibid., 350.

[13] R. A. Stein refrained from using the term Bön, calling the indigenous sources of the Gesar tradition “nameless.” Stein, 191-229.

[14] From a teaching on the Longchen Nyingtik Guru Yoga, given by Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche in Dordogne, France in August 1984, at the request of Sogyal Rinpoche and the Rigpa Sangha. http://www.rigpawiki.org/index.php?title=Dzogchen.

[15] Geoffrey Samuel, Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993), 228-230.

[16] Carolyn Gimian, “Introduction to Volume Eight,” The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa, Vol. VIII (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2004), xii-xiv.

[17] Kornman, 369-370.

[18] Khenchen Jigme Phüntsok, Lama Mipham’s Miracles: The Sound of the Victorious Battle Drum Which Accompanies the Supplication to Omniscient Mipham Gyatso, translated by Ann Helm (Halifax: Nalanda Translation Committee, 1999), 2.

[19] Trungpa, Sacred Path, 28.

[20] The Shambhala teachings share South Asia’s view of time, with ever-declining conditions of auspiciousness, culminating in the Kāli-yuga. The notion of the degenerate age is the backdrop of the Kālacakra-tantra, providing an opportunity to awaken through the special skillful means of tantra.

[21] Dalai Lama, The Kālacakra Tantra, Rite of Initiation for the Stage of Generation: A Commentary on the Text of Kay-drup-ge-lek-bel-sang-bo, edited by Jeffrey Hopkins (London: Wisdom Publications, 1985), 65; Gyatso, Ornament, 40-49.

[22] Gyatso, Ornament, 40-49.

[23] Shambhala Sādhana, 7.

[24] The Kālacakra-tantra speaks of basic goodness as the primordial mind, nyuk-ma sem.

[25] Mipham J. Mukpo, Shambhala Sadhana (Halifax: Kalapa Court, 2012), 2.

[26] Gyatso, 55.

[27] Chögyam Trungpa, Great Eastern Sun (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1999), 185.

[28]Trungpa, Sacred Path, 46.

[29]Trungpa, Great Eastern Sun, 149.

[30] In Japanese traditions, this is spoken of as wabi-sabi, two of the aesthetic moods that characterize appreciation. For more information, see D. T. Suzuki, Zen and Japanese Culture (Princeton: Bollingen, 1957), Chapter 2, and Andrew Juniper, Wabi-Sabi, The Japanese Art of Impermanence (New York: Tuttle, 2003).

[31]Trungpa, Great Eastern Sun, 111.

[32] VIII.129, Padmakara Translation Group, The Way of the Bodhisattva (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1997), 128.

[33] The great Dzogchen master Paltrul Rinpoche (1808-1887) revived Tibet’s interest in Śāntideva as he emphasized the importance of the Bodhicaryāvatāra as the foundation of Dzogchen practice. His students included Ju Mipham Gyatso, whose work spawned the popularity of Shambhala as a tradition.

[34] Dradul, Supreme Thought, 22.

[35] Dradul, Supreme Thought, 26.

[36] Dradul, Supreme Thought, 49.

[37] Dradul, Supreme Thought, 10.

[38] Dradul, Supreme Thought.

[39] Stanley Wolpert, A New History of India, Seventh Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 88-104.

[40] Dradul, Supreme Thought. In Tibetan, mi’i srid pa zang po, transcribed sometimes as “sepa” and others as “sipa.” See Holly Gayley, “Society as Possibility: On the Semantic Range of the Tibetan Word Sipa,” The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture and Politics, (accessed July 21, 2014). http://www.arrow-journal.org/society-as-possibility.

[41] Dradul, Supreme Thought, 5.

[42] Gayley, “Society as Possibility: On the Semantic Range of the Tibetan Word Sipa,” The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture, and Politics, (accessed July 31, 2014). http://www.arrow-journal.org/society-as-possibility.

[43] Trungpa, Sacred Path, 33.

[44] These vows, roughly analogous to refuge and bodhisattva vows, are the Shambhala Vow and the Enlightened Society Vow, followed by practice of the Shambhala Sādhana: Discovering the Sun of Basic Goodness, composed by Jampal Trinley Dradul (Halifax: The Kalapa Court, 2012).

[45] R. A. Stein, Tibetan Civilization, translated by J. E. Stapleton Driver (Stanford: Stanford University, 1972), 202-212; Robin Kornman, “The Thirteen Dralas of Tibet,” (Halifax: Nalanda Translation Committee), 3 (accessed July 17, 2014). http://nalandatranslation.org/media/Thirteen-Dralas-of-Tibet-by-Robin-Kornman.pdf

[46] Stein, Tibetan Civilization, 223-224.

[47] Kornman, “Thirteen Dralas,” 3.

[48] Trungpa, Sacred Path, 109.

[49] Trungpa, Sacred Path, 126.

[50] Trungpa, Sacred Path, 129.

[51] Sakyong Mipham wrote that perhaps the reason his father spoke of “creating” had to do with the mood of the times in which he taught, a mood that emphasized dismantling, destroying. Perhaps the word “create” brought encouragement to “bolster humanity’s confidence in its ability to create a better world.” Sakyong Mipham, The Shambhala Principle: Discovery Humanity’s Hidden Treasure (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2012), 36.

[52] Sakyong, Shambhala Principle, 31.

[53] Trungpa, Shambhala, 94.

[54] Sakyong, Shambhala Principle, Chapter 8.

[55]Chögyam Trungpa. Stafa. “Crazy Wisdom – The World Needs Your Help.” MP3, 0.40. (accessed July 16, 2014). http://m.stafaband.info/download/mp3/X3HIFIZIzLk.html

[56] Adam Lobel, “Practicing Society,” The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture, and Politics, (accessed November 6, 2014), http://www.arrow-journal.org/practicing-society

[57] Robert Aitken, The Mind of Clover (Toronto: HarperCollins, 1984), 3-15; Kenneth Kraft, “Prospects of a Socially Engaged Buddhism,” Inner Peace, World Peace: Essays on Buddhism and Nonviolence, edited by Kenneth Kraft (Albany: State University of New York Press), 11-30.

[58]Thich Nhat Hanh, “Please Call Me by My True Names,” in Fred Eppsteiner, The Path of Compassion (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1988), 33.

[59]Tenzin Gyatso (HH XIVth Dalai Lama), “Hope for the Future,” in Fred Eppsteiner, The Path of Compassion (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1988), 7.

Bibliography

Aitken, Robert. The Mind of Clover. Toronto: HarperCollins, 1984, 3-15.

Arnold, Edward A. As Long As Space Endures: Essays on the Kālacakra Tantra in Honor of H. H. the Dalai Lama. Ithaca: Snow Lion, 2009.

Bernbaum, Edwin. The Way to Shambhala: A Search for the Mythical Kingdom Beyond the Himalayas. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor/Doubleday Books, 1980.

Dalai Lama, “Hope for the Future,” in Fred Eppsteiner, The Path of Compassion. Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1988.

Dalai Lama, The Ethics for a New Millenium. New York: Penguin Books, 2001.

Dalai Lama. The Kālacakra Tantra, Rite of Initiation for the Stage of Generation: A Commentary on the Text of Kay-drup-ge-lek-bel-sang-bo, edited by Jeffrey Hopkins. London: Wisdom Publications, 1985.

Dhargyey, Geshe Lharampa Ngawang. A Commentary on the Kālacakra Tantra. Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 1994.

Dradul, Jampal Trinley. Shambhala Sadhana: Discovering the Sun of Basic Goodness. Halifax: Kalapa Court, 2012.

Dradul, Jampal Trinley. The Supreme Thought. Halifax & Cologne: Dragon Books, 2013.

Gayley, Holly. “Society as Possibility: On the Semantic Range of the Tibetan Word Sipa,” The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture and Politics, (accessed July 21, 2014). http://www.arrow-journal.org/society-as-possibility.

Gimian, Carolyn. “Introduction to Volume Eight,” The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa, Vol. VIII. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2004.

Gyatso, Khedrup Norsang. Ornament of Stainless Light: An Exposition of the Kālacakra-tantra (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2004)

Juniper, Andrew. Wabi-Sabi, The Japanese Art of Impermanence. New York: Tuttle, 2003.

Kraft, Kenneth. “Prospects of a Socially Engaged Buddhism,” Inner Peace, World Peace: Essays on Buddhism and Nonviolence, edited by Kenneth Kraft. Albany: State University of New York Press, 11-30.

Kornman , Robin, Sangye Khandro, and Lama Chönam, tr. The Epic of Ling: Gesar’s Magical Birth, Early Years, and Coronation as King. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2012.

Kornman, Robin. “The Influence of the Epic of King Gesar of Ling on Chögyam Trungpa,” Recalling Chögyam Trungpa, edited by Fabrice Midal. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2005.

Kornman, Robin. “The Thirteen Dralas of Tibet,” (Halifax: Nalanda Translation Committee), 3, (accessed July 17, 2014). http://nalandatranslation.org/media/Thirteen-Dralas-of-Tibet-by-Robin-Kornman.pdf.

Lobel, Adam. “Practicing Society,” The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture and Politics, (accessed November 6, 2014), http://www.arrow-journal.org/practicing-society

Mipham, Sakyong. The Shambhala Principle: Discovery Humanity’s Hidden Treasure. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2012.

Nhat Hanh, Thich. “Please Call Me by My True Names,” in Fred Eppsteiner, The Path of Compassion (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1988).

Newman, John. “Itineraries to Śambhala,” Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre, Jose Ignatio Cabezon and Roger R. Jackson, ed. Ithaca: Snow Lion, 1996.

Padmakara Translation Group. The Way of the Bodhisattva. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1997.

Phüntsok, Khenchen Jigme. Lama Mipham’s Miracles: The Sound of the Victorious Battle Drum Which Accompanies the Supplication to Omniscient Mipham Gyatso, translated by Ann Helm. Halifax: Nalanda Translation Committee, 1999.

Samuel, Geoffrey. Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993.

Stearns, Cyrus. The Buddha From Dölpo: A Study of the Life and Thought of the Tibetan Master Dölpopa Sherab Gyaltsen, 2nd Edition. Ithaca: Snow Lion, 2010.

Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization, translated by J. E. Stapleton Driver. Stanford: Stanford University, 1972.

Suzuki, D. T. Zen and Japanese Culture. Princeton: Bollingen, 1957.

Trungpa, Chögyam. Great Eastern Sun. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1999.

Trungpa, Chögyam. Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1984.

Trungpa , Chögyam. Stafa. “Crazy Wisdom – The World Needs Your Help.” MP3, 0.40, (accessed July 16, 2014). http://m.stafaband.info/download/mp3/X3HIFIZIzLk.html.

Wallace, Vesna. The Kālacakratantra: The Chapter on the Individual Together with the Vimalaprabhā. New York: American Institute of Buddhist Studies, Columbia University, 2004.

Wolpert, Stanley. A New History of India, Seventh Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Judith Simmer-Brown, Ph.D., is Distinguished Professor of Contemplative and Religious Studies at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, where she has taught since 1978. She is the Dean of the Shambhala International Teachers’ Academy, and teaches internationally for Shambhala as an acharya—a senior teacher. Her teaching specialties are meditation practice, Shambhala teachings, Buddhist philosophy, tantric Buddhism, and contemplative higher education. Her book, Dakini’s Warm Breath (Shambhala 2001), explores the feminine principle as it reveals itself in meditation practice and everyday life for women and men. She has also edited Meditation and the Classroom: Contemplative Pedagogy for Religious Studies (SUNY 2011). She had her husband, Richard, have two adult children and three grandchildren.

From: The Arrow

Scott Robbins and Sarah Lipton are thoroughly delighted to introduce their beautiful baby girl to the Shambhala world. Odessa Rose Lipton Robbins was born on February 5th, 2015 after a beautiful labor and birth at home. She is a big girl, weighing in at 9 lbs, 9 oz and 21 3/4 inches. The birth was declared “perfect” by the midwives present, and the new family are luxuriating in each other’s health, joy, love and presence.

Scott Robbins and Sarah Lipton are thoroughly delighted to introduce their beautiful baby girl to the Shambhala world. Odessa Rose Lipton Robbins was born on February 5th, 2015 after a beautiful labor and birth at home. She is a big girl, weighing in at 9 lbs, 9 oz and 21 3/4 inches. The birth was declared “perfect” by the midwives present, and the new family are luxuriating in each other’s health, joy, love and presence.